Interview: Friday, 8 March 2024

To coincide with International Women’s Day 2024 on 8 March, we asked Assistant Professor Khadija van der Straaten from the Department of Business-Society Management at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, about her research into the persistent and pervasive societal issue of gender inequality – more specifically about the differences in wages of employees who are fathers and mothers working in multinational organisations. The study was inspired by her own experience during the Covid-19 pandemic. She found that examining the overvaluation of masculinity in firms rather than the undervaluation of women could help in addressing some of the underlying causes of inequalities, and her research indicates that policies targeted at women may not mitigate the positive biases towards men and masculine corporate cultures. A critical evaluation of gender-related policies, especially in multinationals, is still necessary, she concluded.

What inspired you to research this? You've done work on gender equality in businesses before.

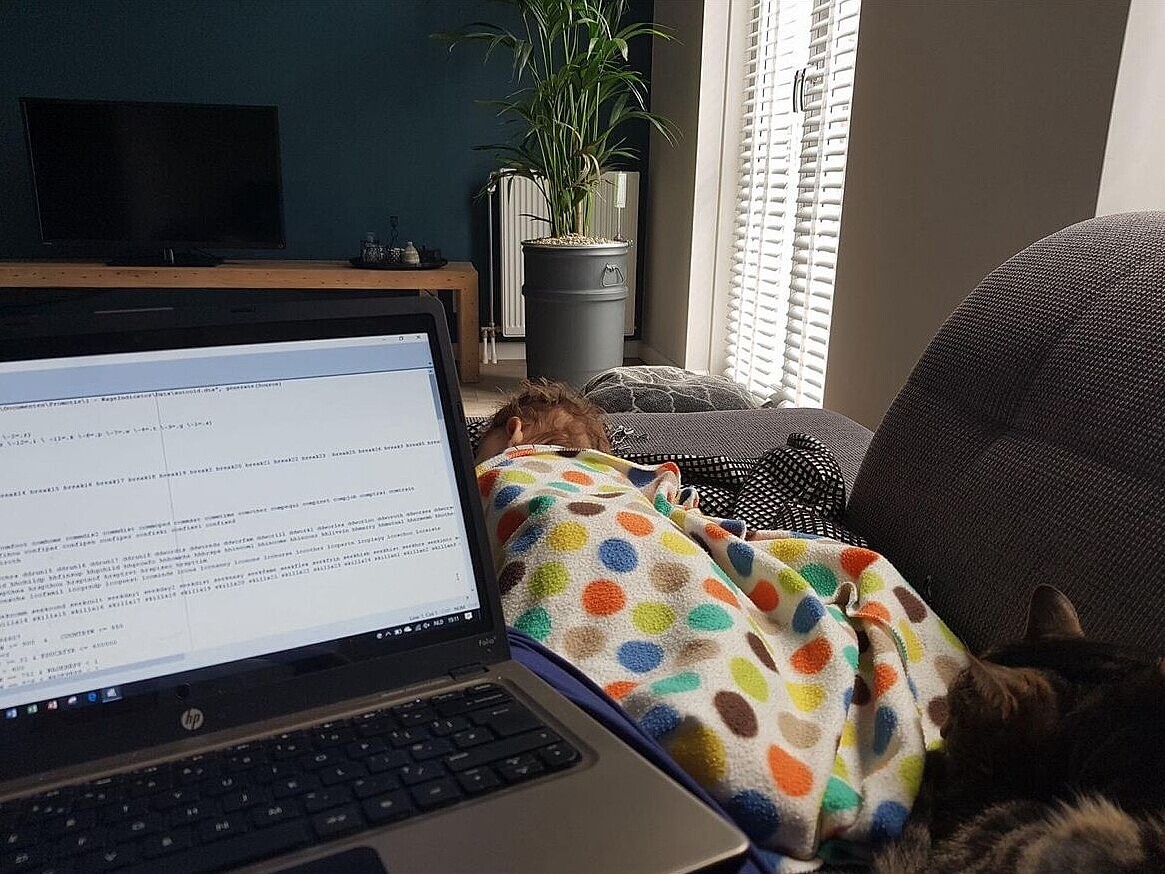

KS: “During the pandemic I was at home with my kids. At the time there was plenty of discussion about the fact that all kinds of responsibilities come down onto mothers. As a single mother, it was extra challenging for me to have the kids at home while I was teaching online and continuing with my work researching international business in the evenings. While I have a great community of neighbours that helped each other keeping an eye on all the kids outside, the oldest would occasionally come to me when I was giving lessons. Luckily my youngest slept a lot."

“I read a lot about how parents combine their work and home life, and how the effects of being a working parent are very different for mothers compared to fathers. I read about the fatherhood bonus and wondered how multinationals and local companies would compare. There was also some personal curiosity: how does this play out in my area of research, in international business? This is where the work-life balance can be exceptionally demanding because of international travel, working across time zones, and a competitive and masculine corporate culture.”

I think a lot of our female readers experienced this during the pandemic. And maybe our male readers never realised they benefitted from having children? So what were your findings?

“I couldn’t collect any data during the lockdowns, but I already had data about wages collected for my other research project on the gender wage gap and immigrant wage gap at multinational organisations – and it happened to include information about children that I could use.” Dr Van der Straaten compared the wages of fathers, mothers, and employees without children across multinational organisations and locally operating firms. Her analysis included over 36,500 employees across 57 countries."

“I found that fathers received a wage premium compared to their childless male peers. This premium was US$2 per hour in multinationals, but only half that, US$1 per hour, in local firms. Mothers suffered a wage penalty from having children, but that this penalty was comparable in both multinationals and local firms.”

Wow. So while mothers are penalised, fathers are given bonuses?! What do you think companies should do with this information?

“The outcome of my study challenges commonly held assumptions about the causes and cures of gender pay inequity related to women’s characteristics and life patterns.

“Policies targeted at women may not lessen the positive biases towards men and masculine corporate cultures. This is also relevant for other groups of employees who deviate from masculine norms – for example those who are transgender, who identify as non-binary, or are fathers who take on non-traditional gender roles – and have been found to face considerable bias in the workplace. A critical evaluation of gender-related policies, especially in multinationals seems necessary."

“Businesses could start by setting up their organisation for more gender equality by thinking who has the advantages, not just focusing on who is disadvantaged."

So there is quite some work to be done. So what do you see as the most important conclusion?

“We are not only paying women too little; we are also paying men too much. This is not just a matter of being male. Masculine men are valued, perhaps overvalued, more often. Mothers are still penalised, and there is work to be done in supporting them at work and at home."

“The most striking aspect to come out of this study is that while there’s lots of discussion about what women should do differently – like doing less part-time work, or improving their skills for negotiating salary and working conditions – we don't even consider that we might be overestimating men, and may need to reward them differently. Setting up organisations for more gender equality means not just thinking about the disadvantaged people, but thinking about the advantaged people.”

What would you advise businesses that would like to address this?

“I’ve submitted applications for grants so I can start looking at solutions. There are already policies about it in governments and companies, but multinationals operate in a range of cultures so it’s more complicated for them. We should be looking at which policies work and which don't work to improve the wage gaps for genders, immigrants, and parenthood.”

The paper has been published in the Journal of International Business Studies under the title Parenthood wage gaps in multinational enterprises

Science Communication and Media Officer

Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University (RSM) is one of Europe’s top-ranked business schools. RSM provides ground-breaking research and education furthering excellence in all aspects of management and is based in the international port city of Rotterdam – a vital nexus of business, logistics and trade. RSM’s primary focus is on developing business leaders with international careers who can become a force for positive change by carrying their innovative mindset into a sustainable future. Our first-class range of bachelor, master, MBA, PhD and executive programmes encourage them to become to become critical, creative, caring and collaborative thinkers and doers.